|

CÁCERES IN PUERTO

RICO - their origins?

//www.wajszczuk.pl/english/drzewo/puerto.htm

Puerto Rico -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puerto_Rico

- officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (Spanish:

Estado Libre Asociado de

Puerto Rico), is an

unincorporated territory

of the

United States,

located in the northeastern

Caribbean

east of the

Dominican Republic

and west of both the

United States Virgin Islands

and the

British Virgin Islands.

(…) Originally populated for centuries by an

aboriginal

people known as

Taíno,

the island was claimed by

Christopher Columbus

for Spain during his second voyage to the Americas on November

19, 1493. (…) Spain held Puerto Rico for over 400 years,

despite attempts at capture of the island by the French, Dutch,

and British. In 1898, Spain ceded the archipelago, as

well as the Philippines, to the United States as a result of its

defeat in the

Spanish–American War

under the terms of the

Treaty of Paris of 1898.

In 1917, the U.S. granted citizenship to Puerto Ricans; Below

are listed (my wife) Carmen’s known ancestors in Puerto Rico:

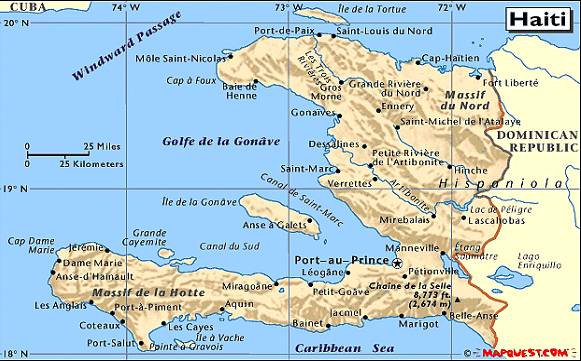

Felipe Cáceres-?/Inocencia

Vasquez-? (? - ?) - from Cabo

Rojo,

Puerto Rico

Juan de Dios Cáceres-Vasquez/Carmela Martinez-Colberg (?

- ?)

Juan de Dios Cáceres-Vasquez/Carmela Martinez-Colberg (?

- ?)

Juan Silvestre Cáceres-Martinez (1897-1972)/Carlina

Ortiz-Ramirez-(Mercado) (1904-1968)

Juan Silvestre Cáceres-Martinez (1897-1972)/Carlina

Ortiz-Ramirez-(Mercado) (1904-1968)

During the process of gathering material for reconstructing the

Family Tree of the Wajszczuk Family, initially of its branch

from Siedlce in Poland and subsequently reaching far into the

past to its roots, we initiated gathering information about the

Family of my wife Carmen, who was born in Cabo Rojo, Puerto

Rico. Initially information was gathered from members of her

immediate family, then from her more distant relatives living in

Puerto Rico, during numerous visits there and trips around the

island. All these were oral reminiscences and the information

was often incomplete and lacking some of the details, in

particular some dates. The memory encompassed only three earlier

generations. No written documents were available; some members

of the family left Cabo Rojo and spread to other locations on

the island. So far we did not have an opportunity to conduct any

searches in the parish or secular archives. A brief review of a

recent monograph by Luis M. Diaz Soler:”PUERTO

RICO

DESDE SUS ORIGENES HASTA EL CESE DE LA DOMINACION ESPAÑOLA - (Puerto

Rico - from the earliest times to the end of Spanish domination)

1994

Universidad de Puerto Rico. ISBN-0-8477-0177-8, revealed only a

very few entries of the names of interest to us (see below).

|

Alonso de Cáceres |

– 1521 was mentioned as a

“mayordomo” of the San Juan Cathedral (this was the year

of its construction). |

|

Ortiz, Diego |

-

1565

– perished fighting the Indians at the river Guayama |

|

Ortiz, José Maria |

- 1819

– in opposition to governor Meléndez |

|

Ortiz Renta(s), José Luciano |

-

1820

– Provincial Deputy |

| |

- 1822 – member of the

“Administration … of Public Works" |

|

Ortiz Reata, José

|

– year? - elector for the Office

of the Presecutor General |

Initial Internet search, followed by a Google search, and based

predominantly on information provided by Wikipedia, revealed

several additional Cáceres names in the “New World”, appearing

earliest and most commonly in Hispaniola (Dominican Republic)

but also occasionally in other countries settled by the Spanish

explorers. I also remembered that Carmen mentioned on several

occasions her early recollections from childhood that her

farther spoke with great pride of their ancestors that

they were “noble”, proud, important and “people of substance”.

No other details survived in the family concerning their origin

and fates in the “New World”. Early findings from the review in

Wikipedia (summarized below) revealed the existence in the 19th

century of at least three Cáceres families in the neighboring

Dominican Republic, some of their members holding high

offices. Thus, it is possible that in the course of

turbulent events there early in the 19th century, perhaps, some

of them decided to move to Puerto Rico – our search will

continue to prove it! The last name probably originates from the

town or province of Cáceres.

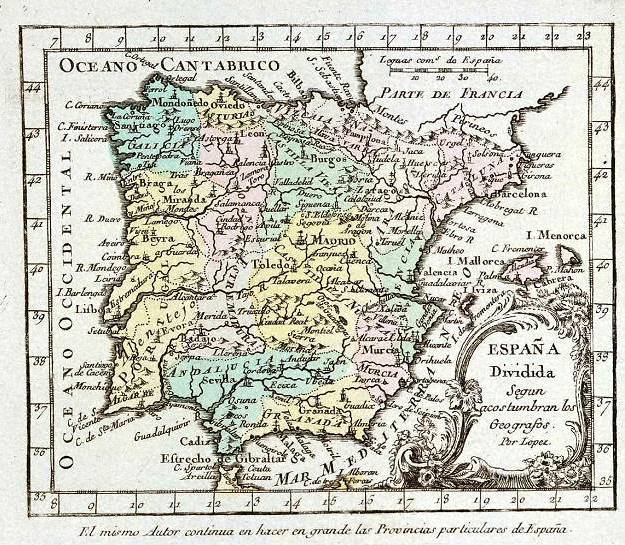

Spain – 1757 map (including Portugal)

Extremadura -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extremadura

Extremadura

(English

/ˌɛkstrɨməˈdʊrə/;

Spanish: [e(k)stɾemaˈðuɾa];

Extremaduran:

Estremaura

[ehtɾemaˈuɾa])

is an

autonomous community

of western

Spain whose

capital city is

Mérida. Its

component

provinces are

Cáceres and

Badajoz. It is

bordered by

Portugal to

the west. To the north it borders

Castile and León

(provinces of

Salamanca and

Ávila); to the

south, it borders

Andalusia

(provinces of

Huelva,

Seville, and

Córdoba); and

to the east, it borders

Castile–La Mancha

(provinces of

Toledo and

Ciudad Real).

Its official language is Spanish.

Lusitania, an

ancient

Roman province

approximately including current day Portugal (except for the

northern area today known as

Norte Region)

and a central western portion of the current day Spain, covered

in those times today's Autonomous Community of Extremadura.

Mérida (now

capital of Extremadura) became the capital of the Roman province

of Lusitania, and one of the most important cities in the

Roman Empire.

It was part of the Umayyad

Caliphate of Córdoba,

but after its definite collapse in 1031 the Caliphate fragmented

into small regional kingdoms, and the lands of Extremadura were

included in the

Taifa of Badajoz

on two taifa periods. (…) After the

Almohad

disaster in

Navas de Tolosa

(1212), Extremadura fell to the troops led by

Alfonso IX of León

in approx. 1230.

Extremadura

was the source of many of the initial Spanish conquerors (conquistadores)

and settlers in America.

Hernán Cortés,

Francisco Pizarro,

Gonzalo Pizarro,

Juan Pizarro,

Hernando Pizarro,

Hernando de Soto,

Pedro de Alvarado,

Pedro de Valdivia,

Inés Suárez,

Alonso de Sotomayor,

Francisco de Orellana,

Pedro Gómez Duran y Chaves, and

Vasco Núñez de Balboa

were all born in Extremadura, and many towns and cities in

America carry a name from their homeland:

Spanish rule before

appointment of Viceroy (1492-1536)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Viceroys_of_New_Spain#The_Indies

The (West)

Indies

1492 – 1499

Christopher

Columbus,

as governor and viceroy of the Indies

1499 – 1502

Francisco de

Bobadilla,

as governor of the Indies

1502 –

1509

Nicolás de Ovando y

Cáceres,

as

governor of the Indies – (see below)

1509 – 1518

Diego Columbus,

as governor of the Indies until 1511, thereafter as viceroy

1518 – 1524

Diego Velázquez de

Cuéllar,

as

adelantado

(governor-general) of Cuba

Cáceres

– conquistador born (and died) in Spain

|

Nicolás Ovando y Cáceres

was born in Brozas in 1460. Born into a

noble and pious family, second son of

Diego

Fernández de Cáceres y Ovando,

1st Lord of the

Manor House

del Alcázar Viejo, and his first wife Isabel

Flores de las Varillas (a distant relative of

Hernán

Cortés),

Ovando entered the military

Order of

Alcántara,

where he became a Master (Mestre

or Maitre) or a

Commander-Major

(Comendador-Mayor). This Spanish military

order, founded in 1156, resembled the

Order of

Templars, with

whom it fought the Moors during the

Reconquista.

His elder brother was

Diego de

Cáceres y Ovando.

His ancestor was Juan

Blázquez de Cáceres, who was born in

Ávila

and was at the Conquest (from the Arabs) of

Cáceres

on April 23, 1229,

from which he took his surname.

As

Commander

of

Lares de

Guahaba Ovando

became a favorite of the Spanish

Catholic

Monarchs,

particularly of the pious

Queen

Isabella I.

Thus, in response to complaints from

Christopher

Columbus and

others about

Francisco de

Bobadilla the

Spanish monarchs on September 3, 1501, appointed

Ovando to replace Bobadilla. Ovando become the

third Governor and Captain-General of the

Indies, Islands and Firm-Land of the Ocean Sea.

Thus, on February 13, 1502, he sailed from Spain

with a fleet of thirty ships. It was the largest

fleet that had ever sailed to the New World. The

thirty ships carried 30,500 colonists. Unlike

Columbus's

earlier voyages, this group of colonists was

deliberately selected to represent an organized

cross-section of Spanish society. The Spanish

Crown intended to develop the

West Indies

economically and thereby expand Spanish

political, religious, and administrative

influence in the region. Along with him also

came

Francisco Pizarro,

who would later explore western

South America

and conquer the

Inca Empire.

Another ship carried

Bartolomé de las Casas,

who became known as the 'Protector of the

Indians' for exposing atrocities committed by

Ovando and his subordinates. Hernán Cortés,

a family acquaintance and distant relative, was

supposed to sail to the Americas in this

expedition, but was prevented from making the

journey by an injury he sustained while

hurriedly escaping from the bedroom of a married

woman of

Medellín.[1]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicol%C3%A1s_de_Ovando_y_C%C3%A1ceres |

The

Order of Alcántara (Spanish:

Orden de

Alcántara),

also called the Knights of St. Julian,[1]

was originally a military order of

León,

founded in 1166[2]

and confirmed by Pope Alexander III in 1177.[3]

Diego de Cáceres y Ovando,

first-born son of

Diego Fernández de Cáceres y Ovando,

1st Señor of the

Manor House

del Alcázar Viejo, and first wife Isabel Flores de las

Varillas, a distant relative of

Hernán Cortés

|

|

|

Caceres, Torre Ciguenas |

was the 2nd Señor of the

House

de las Cigüeñas, at the

Plaza de San Mateus of

Cáceres,

in which he succeeded in 1487, Corregedor of

Valladolid,

Comendador-Mayor of

Alcántara,

in which conventual church he was interred.

Ancestors of Diego de

Cáceres y Ovando and Fray Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres were:

Juan

Blázquez de Cáceres,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Bl%C3%A1zquez_de_C%C3%A1ceres,

the Conqueror of Cáceres, who was a Spanish

soldier and nobleman. Juan Blázquez de Cáceres was born in

Ávila and was at the Conquest of Cáceres (from the

Arabs), on April 23, 1229, from which he took his

surname. He was married to Teresa Alfón and

- had at least one son, Blazco Múñoz de Cáceres,

who died at 90 years and lived in

Cáceres

in 1270,

married to Pascuala Pérez, daughter of

Pascual Pérez and wife Menga Marín,

- parents of Blazco Múñoz de Cáceres,

Founder

and 1st Lord of the Majorat of the same name, and

García Blázquez de Cáceres, who by

one Marina Pérez had

Fernán Blázquez de Cáceres,

2nd

Lord

of the

Majorat

de Blazco Múñoz. They

were the ancestors

of the Marqueses de

Alcántara

(de Villavicencio del

Cuervo, May 13,

1667).[1]

Spanish conquests and expansion in the

Caribbean region

1492 - Colony of Santo Domingo -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colony_of_Saint-Domingue

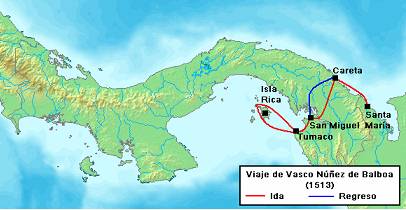

1513

- Balboa's

travel route to the “South Sea” (Pacific Ocean).

Vasco

Núñez de Balboa

(c. 1475 – around January 12–21, 1519[1]),

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasco_N%C3%BA%C3%B1ez_de_Balboa

- was a

Spanish

explorer,

governor,

and

conquistador.

In September 1510, he founded the first permanent

settlement on mainland American soil, and called it

Santa María la Antigua

del Darién. He is best

known for having crossed the

Isthmus of Panama

to the

Pacific Ocean

in 1513, becoming the first European to lead an expedition

to have seen or reached the Pacific from the

New World.

1513 -

Tierra Firme

-

Castilla de Oro

(Colombian-Panamanian border region)

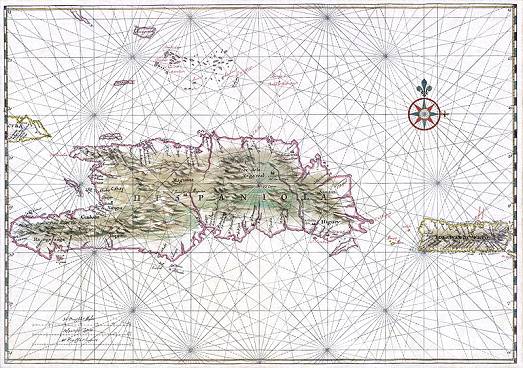

Early map of Hispaniola and

Puerto Rico,

c. 1639.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo

and de las Casas documented that the island was called

Haití ("Mountainous Land") by the Taíno.

Taino Indians -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ta%C3%ADno_people

Many

people identify as descendants of the Taíno, most

notably among the

Puerto Ricans

and Dominicans, both on the islands and on the

United States

mainland. The concept of "living Taíno" has proved

controversial. The people and society were long declared

extinct.[52]

The Taíno were seafaring

indigenous peoples

of the

Bahamas,

Greater Antilles,

and the northern

Lesser Antilles.

They were one of the

Arawak peoples

of

South America,[1]

and the

Taíno language

was a member of the

Arawakan

language family

of northern South America.

At the

time of

Columbus'

arrival in 1492, there were five Taíno

chiefdoms

and territories on

Hispaniola

(modern-day

Haiti

and

Dominican Republic),

each led by a principal

Cacique

(chieftain),

to whom tribute was paid.At the time of Columbus'

arrival in 1492, there were five Taíno chiefdoms and

territories on Hispaniola (modern-day Haiti and

Dominican Republic), each led by a principal Cacique

(chieftain), to whom tribute was paid.

The

five caciquedoms of Hispaniola at the time of the

arrival of Christopher Columbus. -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Haiti

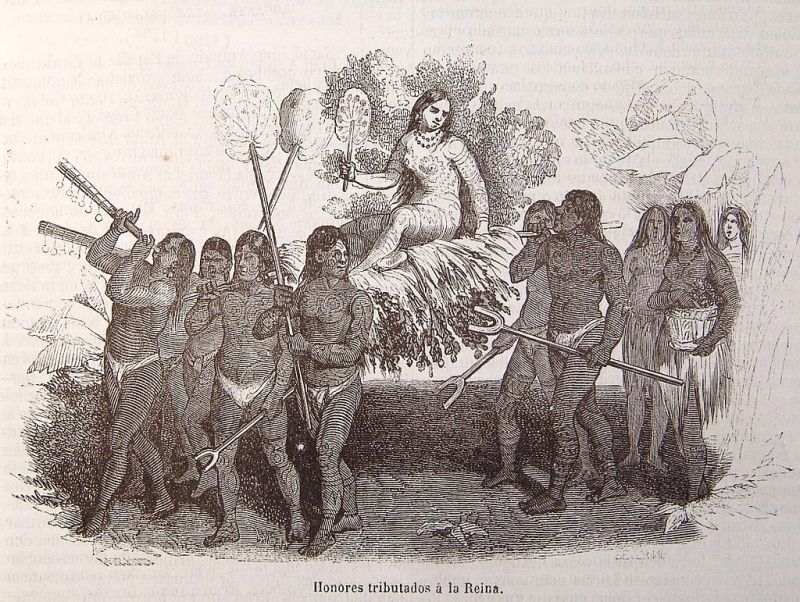

Taino Queen (”caciqua”), called

Anacaona, “The Golden Flower”, at the time of Spanish

arrival in Hispaniola

Reception from Anacaona on

Hispaniola for Bartolomew Columbus and his party

Cuba,

the largest island on the

Antilles,

was originally divided into 29 chiefdoms. Most of the

native settlements later became the site of Spanish

colonial cities retaining the original Taíno names, for

instance;

Havana,

Batabanó,

Camagüey,

Baracoa

and

Bayamo.[2]

Puerto Rico

also was divided into

chiefdoms. As the hereditary head chief of Taíno tribes,

the cacique was paid significant tribute. At the time of

the

Spanish conquest,

the largest Taíno population centers may have contained

over 3,000 people each (…)

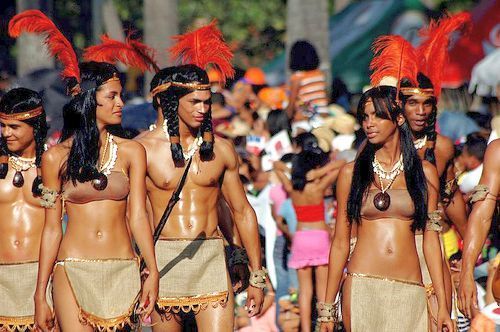

Dominican

girls at carnival, in Taíno garments and makeup (2005)

The Taíno were

historically enemies of the neighboring

Carib

tribes, another group with origins in

South America,

who lived principally in the

Lesser Antilles.[3]

Frank Moya Pons, a

Dominican historian, documented that Spanish colonists

intermarried with Taíno women. Over time, some of their

mestizo descendants intermarried with

Africans,

creating a tri-racial

Creole

culture. 1514

census

records reveal that 40% of Spanish men in the Dominican

Republic had Taíno wives.[52]

A 2002 study conducted in

Puerto Rico suggests that over 61% of the population

possess Amerindian mtDNA.[54]

On average Puerto Ricans

possess approximately 10-15%

Native American

MtDNA, most of it Taíno in origin; it is mixed into the

genome

in short pieces, consistent with a single short period

of unions between the races several hundred years ago.[56]

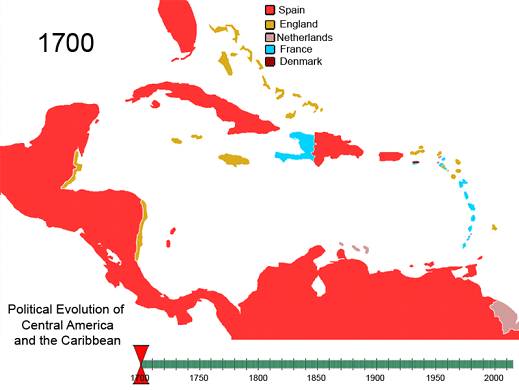

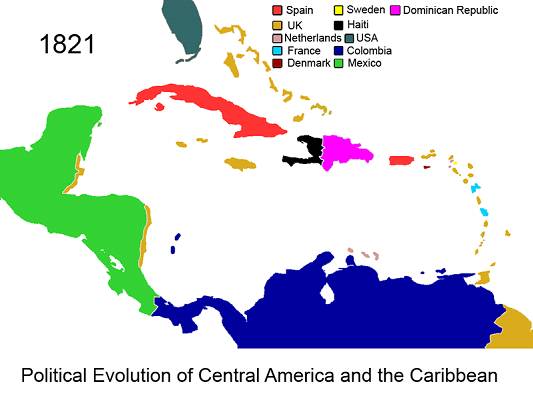

Caribbean 1700 -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Territorial_evolution_of_the_Caribbean

At the time of the

European

discovery of most of the islands of the Caribbean, three

major

Amerindian

indigenous peoples

lived on the islands: the

Taíno

in the

Greater Antilles,

The Bahamas

and the Leeward Islands; the Island

Caribs

and

Galibi

in the

Windward Islands;

and the

Ciboney

in western

Cuba.

The Taínos are subdivided into Classic Taínos, who

occupied Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, Western Taínos, who

occupied Cuba, Jamaica, and the Bahamian archipelago,

and the Eastern Taínos, who occupied the Leeward

Islands.[1]

Trinidad

was inhabited by both

Carib speaking

and

Arawak-speaking

groups.

Hispaniola

-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hispaniola

(Spanish:

La Española;

Haitian Creole:

Ispayola;

Taíno:

Ayiti[3])

is the

22nd-largest island

in the world, located

in the

Caribbean

island group,

the

Greater Antilles.

It is the second largest island in the

Caribbean

after

Cuba,

the

tenth-most-populous

island in the world, and the most populous in the

Americas.

The island contains two

sovereign nations,

with the

Dominican Republic

occupying the easternmost 64% of the island's area, and

Haiti

the remainder. It is the site of the first European

colonies founded by

Christopher Columbus

on his voyages in 1492 and 1493. The

colonial terms

Saint-Domingue

and

Santo Domingo

are sometimes still applied to the whole island,

although these names refer, respectively, to the

colonies that became Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Christopher Columbus

arrived at the island during his first voyage to the

Americas in 1492, where his flagship, the

Santa Maria,

sank after running aground on Christmas Day. During his

arrival, he founded the settlement of

La Navidad

on the north coast of present-day

Haiti.

On his return the subsequent year, following the

disbandment of La Navidad, Columbus quickly founded a

second settlement farther east in present-day

Dominican Republic,

La Isabela.

(…) After being destroyed by a

hurricane,

it was rebuilt on the opposite side of the Ozama River

and called

Santo Domingo.

It is the oldest permanent European settlement in the

Americas.

In 1665,

French colonization

of the

island was officially recognized by

King Louis XIV.

The French colony was given

the name

Saint-Domingue.

French Saint-Domingue

-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Haiti

- (1625–1789): Its brief history:

The Foundation of a Colony (1625–1711) -

Under the 1697

Treaty of Ryswick,

Spain officially ceded the western third of Hispaniola

to France which renamed the colony

Saint-Domingue.

Saint-Domingue

quickly came to overshadow the east in both

wealth

and

population.

“The

Pearl of the Antilles” (1711–1789) -

one of the richest colonies in the 18th century

French empire.

An estimated 790,000 African slaves (accounting in

1783–91 for a third of the entire

Atlantic slave trade)

worked on the sugar and coffee plantations. They

produced about 40 percent of all the sugar and 60

percent of all the coffee consumed in Europe;

Revolutionary period

(1789–1804) – the rising of slaves, extreme cruelty of

war, Napoleon was defeated (1802-1804) -

In a final act of retribution, the remaining French

were slaughtered by Haitian military forces.

One exception

was a military force of

Poles

from the

Polish Legions

that had fought in Napoleon's army. Some of them refused

to fight against blacks, supporting the principles of

liberty; also, a few Poles (around 100) actually joined

the rebels (W³adys³aw

Franciszek Jab³onowski

was one of the Polish generals). Therefore, Poles were

allowed to stay and were spared the fate of other

whites. About 400 of the 5 280 Poles chose this option.

http://haitikiskeyabohio.blogspot.com/2012/12/polish-descendants-in-haiti.html

W³adys³aw Franciszek Jab³onowski

(25 October 1769–29 September 1802) was a

Black

Polish

and

French

general.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W%C5%82adys%C5%82aw_Franciszek_Jab%C5%82onowski.

He was of mixed ancestry - the illegitimate child of

Maria Dealire, an English aristocrat, and an

unidentified African. He acquired the nickname "Murzynek"-

(“Negrito”).[1]

Maria Dealire's husband, the Polish nobleman Konstanty

Jab³onowski, accepted him as his son. (…) In 1783 he was

admitted to the French military academy at

Brienne-le-Château.

There he was a schoolmate of

Napoleon

and

Davout.

(…) In 1794 he fought in

Tadeusz Koœciuszko's

uprising

against Tsarist Russia. He participated in battles of

Szczekociny,

Warsaw,

Maciejowice,

and at

Praga.

In 1799 he was made General of Brigade of the

Polish legions.[2]

(…) From 1801 he was the leader of

Legia Naddunajska.

He was sent on his own request to

Haiti

in May 1802 (before the decision to send the rest of the

Polish legions). There he worked to put down the

Haitian Revolution.

Jab³onowski died from

yellow fever

on September 29, 1802 in

Jérémie,

Haiti.[2]

He is mentioned in

Adam Mickiewicz's

famous epic poem

Pan Tadeusz

in the context of a veteran of the Polish legions (…)

Haiti

- The name

Haïti

was adopted (in

1801) by Haitian revolutionary

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

as the official name of independent Saint-Domingue, as a

tribute to the Amerindian predecessors. Quisqueya

(from Quizqueia) although used on both sides of

the island is mostly adopted in the Dominican Republic.

Spanish Hispaniola

-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Haiti

-

(1492–1625)

Christopher Columbus

established a settlement,

La Navidad,

near the modern town of

Cap Haitien.

It was built from the timbers of his wrecked ship

Santa María,

during his

first voyage

in December 1492. When he returned in 1493 on his second

voyage he found the settlement had been destroyed and

all 39 settlers killed. Columbus continued east and

founded a new settlement at

La Isabela

on the territory of the present day

Dominican Republic

in 1493. The capital of the colony was moved to

Santo Domingo

in 1496, on the south west coast of the island also in

the territory of the present day Dominican Republic. The

Spanish returned to western Hispaniola in 1502,

establishing a settlement at Yaguana, near modern day

Léogane.

A second settlement was established on the north coast

in 1504 called Puerto Real near modern

Fort Liberte

– which in 1578 was relocated to a nearby site and

renamed Bayaha.

Dominican Republic

-

When the

French Revolution

abolished

slavery in the colonies on February 4, 1794, it was a

European first,[12]

and when Napoleon reimposed slavery in 1802 it

led to a major upheaval by the emancipated black slaves.

(…) After the French removed the surviving 7,000 troops

in late 1803, the leaders of the revolution declared the

new nation of independent Haiti in early 1804.

(…) France demanded a high payment for compensation

to slaveholders who lost their property, and Haiti

was saddled with unmanageable debt for decades.[14]

It became one of the poorest countries in the Americas,

while the Dominican Republic, whose independence was won

via a very different route[14]

gradually has developed into the largest economy of

Central America

and the

Caribbean.

In the second 1795 Treaty of Basel (July 22), Spain

ceded the eastern two-thirds of the island

of Hispaniola, later to become the Dominican

Republic. (…)

Haitian Revolution

-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haitian_Revolution

The Haitian Revolution

(1791–1804) was a

slave revolt

in the French

colony

of

Saint-Domingue,

which culminated in the elimination of

slavery

there and the founding of the

Republic of Haiti.

The Haitian Revolution was the only slave revolt which

led to the founding of a

state.

(…) The rebellion began with a revolt of black African

slaves in August 21, 1791. It ended in November 1803

with the French defeat at the

battle of Vertières.

Haiti became an independent country on

January 1, 1804.

Within the next ten days,

slaves had taken control of the entire Northern Province

in an unprecedented slave revolt. Whites kept control of

only a few isolated, fortified camps. The slaves sought

revenge on their masters through "pillage, rape,

torture, mutilation, and death".[23]

Because the plantation owners had long feared such a

revolt, they were well armed and prepared to defend

themselves. Nonetheless, within weeks, the number of

slaves who joined the revolt reached some 100,000.

Within the next two months, as the violence escalated,

the slaves killed 4,000 whites and burned or destroyed

180 sugar plantations and hundreds of coffee and indigo

plantations.[23]

By 1792, slave rebels controlled a third of the island.

Apart from granting

rights to the free people of color, the Assembly

dispatched 6,000 French soldiers to the island.[24]

Meanwhile, in 1793, France

declared war on Great Britain. The white planters in

Saint Domingue made agreements with Great Britain to

declare British sovereignty over the islands. Spain, who

controlled the rest of the island of

Hispaniola,

would also join the conflict and fight with Great

Britain against France. The Spanish forces invaded Saint

Domingue and were joined by the slave forces. (…) the

French commissioners

Sonthonax

and Poverel freed the slaves in St. Domingue. It has

recently been estimated that the slave rebellion

resulted in the death of 350,000 Haitians and 50,000

European troops.[26].

One of the most

successful black commanders was

Toussaint L'Ouverture,

a self-educated former domestic slave. (…) After the

British had invaded Saint-Domingue, L'Ouverture decided

to fight for the French if they would agree to free all

the slaves. He brought his forces over to the French

side in May 1794 and began to fight for the French

Republic. Under the military leadership of Toussaint,

the forces made up mostly of former slaves succeeded in

winning concessions from the British and expelling the

Spanish forces. In the end, Toussaint essentially

restored control of Saint-Domingue to France. Toussaint

defeated a British expeditionary force in 1798. In

addition, he led an invasion of neighboring Santo

Domingo (December 1800), and freed the slaves

there on January 3, 1801. (…)

Napoleon Bonaparte

dispatched a

large expeditionary force

of French soldiers and warships to the island, led by

Bonaparte's brother-in-law

Charles Leclerc,

to restore French rule. (…) L'Ouverture was promised his

freedom if he agreed to integrate his remaining troops

into the French army. L'Ouverture agreed to this in May

1802. He was later deceived, seized by the French and

shipped to France. He died months later in prison at

Fort-de-Joux

in the Jura region.[8]

(…)

On 1 January 1804,

Dessalines,

the new leader under the dictatorial 1801 constitution,

declared Haiti a free republic in the name of the

Haitian people,[32]

which was followed by the

massacre of the remaining whites.[33(…)

Fearing a return of French forces, Dessalines first

expanded and maintained a significant military force.

(…)Under the presidency of

Jean Pierre Boyer,

Haiti made reparations to French slaveholders in 1825 in

the amount of 150 million francs, reduced in 1838 to

60 million francs, in exchange for French recognition of

its independence. (…) Haitian forces, led by Boyer,

invaded neighboring

Dominican Republic

in February 1822. This was the beginning of a 22-year

occupation by Haitian forces.[40]

(...)

After three centuries of

Spanish rule, with French and Haitian interludes, the

country became independent in 1821. The ruler,

José Núñez de Cáceres,

intended that the Dominican Republic be part of the

nation of

Gran Colombia,

but he was quickly removed by the Haitian government and

"Dominican" slave revolts. Victorious in the

Dominican War of Independence

in 1844, Dominicans experienced mostly

internal strife

over the next 72 years, and also a brief return to

Spanish rule. (…)

Unification of Hispaniola

-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unification_of_Hispaniola

European colonization

- By

the late 18th century, the island of

Hispaniola

had been divided into two European colonies:

Saint-Domingue,

in the west, governed by France; and

Santo Domingo,

governed by Spain, occupying the eastern five-eighths of

Hispaniola.

In 1804, following black

slave uprisings since 1791, the French colony

declared its

independence as

Haïti. Independence did not come easily, given the

fact that Haiti had been France's most profitable

colony, and the richest in the hemisphere. The colony

was dubbed the Pearl of the Antilles, as a result

of the sugar plantations worked by slaves; sugar had

become a very expensive commodity in Europe.[4]

Meanwhile, on the eastern

side, what was once the

headquarters

of Spanish colonial power in the

New World

historically had fallen into decline. At the time, Spain

had most of its own resources focused on the

Peninsular War

and the various hard-fought

wars to maintain

control of the American mainland.[5]

The economy of Santo Domingo

was stalled, the land largely

unexploited and used for

sustenance farming

and

cattle ranching,

and the population was much lower than in Haiti. The

accounts by the Dominican essayist and politician

José Núñez de

Cáceres cite the

Spanish colony's population at around 80,000, mainly

composed of

European

descendants, mulattos, freedmen, and a few black slaves.

Haiti, on the other hand, was nearing a million former

slaves.

Independence from Spain

- On November 9,

1821 the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo was

toppled by a group led by

José Núñez de

Cáceres, the

colony's former administrator,[6][7]

and the rebels proclaimed independence from the Spanish

crown on November 30, 1821.[8]

The new nation was known as Republic of Spanish Haiti

(Spanish: República del Haití Español), as

Haiti had been the indigenous name of the island.[7]

On December 1, 1821 a constitutive act was ordered to

petition the union of Spanish Haiti with

Gran Colombia.

A group of Dominican

politicians and military officers favored uniting the

newly independent nation with Haiti, as they

sought for political stability under Haitian president

Jean Pierre Boyer,

and were attracted to Haiti's perceived wealth and power

at the time. A large faction based in the northern

Cibao

region were opposed to the union with Gran Colombia and

also sided with Haiti. Boyer, on the other hand, had

several objectives in the island that he proclaimed to

be "one and indivisible": to maintain Haitian

independence against potential French or Spanish attack

or reconquest; to maintain the freedom of its former

slaves; and to liberate the remaining slave minority on

the Dominican side of the island.[8][9][10]

While appeasing the

Dominicans, Jean Pierre Boyer was already in

negotiations with France to prevent an attack by

fourteen French warships stationed near

Port-au-Prince,

the Haitian capital. They soon agreed that France would

sell the territory to the Haitian rebels for 150 million

Francs (more than twice what France had charged the

United States for the much larger

Louisiana territory

in 1803).

The Dominican

nationalists who were against the unification of the

island were at a serious disadvantage if they were to

prevent this from occurring. At the time, they had no

trained military forces whatsoever. The population was

eight to ten times less than Haiti's, and the economy

was stalled. Haiti, on the other hand, had formidable

armed forces, both in skill and sheer size, which had

been hardened in nearly ten years of repelling French

Napoleonic soldiers,

and British soldiers, along with the local colonialists,

and military insurgents within the country. The racial

massacres perpetrated in the later days of the

French–Haitian conflict only added to the determination

of Haitians to never lose a battle.

Unification

- After promising his full support to several Dominican

frontier governors and securing their allegiance, Boyer

entered the country with around 10,000 soldiers in

February 1822, encountering little to no opposition. On

February 9, 1822, Boyer formally entered the capital

city, Santo Domingo after its ephemeral independence ,

where he was met with great enthusiasm and received from

president Núñez de Cáceres the keys to the Palace.[9]

The island was thus united from "Cape Tiburon to Cape

Samana in possession of one government."[8]

The occupation is

recalled by some as a period of strict military rule,

though the reality was far more complex. It led to

large-scale land

expropriations and failed efforts to force

production of export crops, impose military services,

restrict the use of the Spanish language, and

suppress traditional customs. The 22 year

unification reinforced the

Spanish Haitian

people perception of

themselves as different from the

Haitians

in race, language, religion and domestic customs.[1]

This period also definitively ended slavery as an

institution in what became the

Dominican Republic,

though ironically

forms of slavery

still remain an integral part of Haitian culture.[2][3]

In order to raise funds

for the huge indemnity of 150 million francs that Haiti

agreed to pay the former French colonists, and which was

subsequently lowered to 60 million francs, Haiti imposed

heavy taxes on the Dominicans. Since Haiti was unable to

adequately provision its army, the occupying forces

largely survived by commandeering or confiscating food

and supplies at gunpoint. Attempts to

redistribute

land conflicted with the system of communal land tenure

(terrenos comuneros), which had arisen with the

ranching economy, and newly emancipated slaves resented

being forced to grow cash crops under Boyer's Code

Rural.[11]

In rural areas, the Haitian administration was usually

too inefficient to enforce its own laws. It was in the

city of Santo Domingo that the effects of the occupation

were most acutely felt, and it was there that the

movement for independence originated.

Haiti's constitution also forbade white elites from

owning land, and the major landowning families

were forcibly deprived of their properties. Most

emigrated

to

Cuba,

Puerto Rico

(these two being

Spanish possessions

at the time) or

Gran Colombia,

usually with the encouragement of Haitian officials, who

acquired their lands. The Haitians, who associated the

Roman Catholic

Church with the French

slave-masters who had exploited them before

independence, confiscated all church property, deported

all foreign clergy, and severed the ties of the

remaining clergy to the

Vatican.

Santo Domingo's

university, the oldest

in the

Western Hemisphere,

lacking both students and teachers had to close down,

and thus the country suffered from a massive case of

human capital flight.

Although the occupation effectively eliminated colonial

slavery and instated a constitution modeled after the

United States

Constitution

throughout the island, several resolutions and written

dispositions were expressly aimed at converting average

Dominicans into second-class citizens: restrictions of

movement, prohibition to run for public office, night

curfews, inability to travel in groups, banning of

civilian organizations, and the indefinite closure of

the state university (on the alleged grounds of its

being a subversive organization) all led to the creation

of movements advocating a forceful separation from Haiti

with no compromises.

Resistance

- In 1838 a

group of educated nationalists, among them,

Juan Pablo Duarte,

Matías Ramón Mella,

and

Francisco del

Rosario Sánchez

founded a secret society called

La Trinitaria

to gain independence from Haiti. In 1843 they allied

with a Haitian movement that overthrew Boyer in Haiti.

After they revealed themselves as revolutionaries

working for Dominican independence, the new Haitian

president,

Charles

Rivière-Hérard, exiled

or imprisoned the leading Trinitarios. At the

same time,

Buenaventura Báez,

an

Azua

mahogany exporter and deputy in the

Haitian National

Assembly, was

negotiating with the French Consul-General for the

establishment of a French protectorate.

In an uprising timed to

preempt Báez, on February 27, 1844, the Trinitarios

declared independence from Haiti, backed by

Pedro Santana,

a wealthy cattle-rancher from

El Seibo

who commanded a private army of

peons

who worked on his estates. This marked the beginning of

the

Dominican War of

Independence.

The

Unification of Hispaniola

by Haiti lasted twenty-two years, from February 9,

1822 to February 27, 1844. This unification

ended the first brief period of independence in

the nation's history,

the

Republic of Spanish

Haiti, which had been

known as the

Captaincy General of Santo Domingo.

Dominican War of Independence -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dominican_War_of_Independence

The Dominican Independence War gave the

Dominican Republic

freedom from

Haiti

on February 27, 1844. Before the war, the island

of

Hispaniola

had been unified under Haitian rule for a period of 22

years when Haiti

occupied the independent state of Spanish Haiti

in 1822. After the struggles that were made by

Dominican

nationalists to free the country from Haitian control,

they had to withstand and fight against a series of

Haitian incursions that served to consolidate their

independence (1844-1856). After the war Haitian soldiers

would make incessant attacks to try to gain back control

of the nation, but these efforts were to no avail, as

the Dominicans would go on to decisively win every

battle.

Cáceres

– Criollos born in Hispaniola/Dominican Republic

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dominican_Republic

The Criollo

(or "creole" people)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criollo_people)

were a social class in the

caste system

of the

overseas colonies established by Spain

in the 16th century, especially in

Latin America,

comprising the locally born people of pure

Spanish

ancestry.[1]

The

Criollo class ranked below that of the Iberian

Peninsulares,

the high-born (yet class of commoners) permanently

resident colonists born in

Spain.

But Criollos were higher status/rank than all other

castes — people of mixed descent, Amerindians, and

enslaved

Africans.

According to the

casta

system, a Criollo could have up to 1/8 (one

great-grandparent or equivalent)

Amerindian,

ancestry and not lose social place (see

Limpieza de sangre).[2]

In the 18th- and early 19th centuries, changes in the

Spanish Empire's policies towards her colonies (and

their polyglot of peoples) led to tensions between the

Criollos and the Peninsulares.[citation

needed]

The growth of local Criollo political and economic

strength in their separate colonies coupled with their

global geographic distribution, and led them to each

evolve a separate (both from each other and Spain)

organic national personality and viewpoint. Criollos

were the main supporters of the

Spanish American wars of independence.

Map of the Dominican Republic

– indicated are dates and places of births (b.)

and deaths (d.) of the prominent Caceres

personalities listed below

(...)

After three centuries of Spanish rule,

with French and Haitian interludes, the country became

independent in 1821. The ruler,

José Núñez de Cáceres,

intended that the Dominican Republic be part of the

nation of

Gran Colombia,

but he was quickly removed by the Haitian government and

"Dominican" slave revolts. Victorious in the

Dominican War of Independence

in 1844, Dominicans experienced mostly

internal strife

over the next 72 years, and also a brief return to

Spanish rule. (…)

|

President of

Spanish Haiti,

December 31, 1821 – February 9,

1821

|

1) José Núñez de Cáceres Albor

–

born in [the city of] Santo

Domingo in 1772/1779? President in 1821.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jos%C3%A9_N%C3%BA%C3%B1ez_de_C%C3%A1ceres

(This name uses

Spanish

naming customs;

the first or paternal

family

name is

Núñez de Cáceres and

the second or maternal family name is Albor).

José

Núñez de Cáceres

-

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Search&limit=50&offset=50&redirs=1&profile=default&search=Ramon+C%C3%A1ceres

José Núñez de Cáceres Albor (b.

Santo Domingo,

March 14, 1772/1779; †

Ciudad Victoria

(Mexico),

September 11, 1846) was a Dominican

politician and writer. He was the leader of

Dominican independence when

Spain

ruled the country and he was also the first

person in the country to use literature as

weapon of social protest and politics. He was

also the first Dominican

fabulist

and one of the first

criollo

storytellers in

Spanish America.

In addition, he founded the newspaper "El Duende",

the second newspaper created in Santo Domingo.

José Núñez de

Cáceres Albor was born on March 14, 1772 (or

1779), in Santo Domingo. He was the

son of

2ndLt. Francisco

Núñez de Cáceres and María Albor.

His mother died a few days after his birth. He

was raised by his aunt María Núñez de Cáceres.

Since his childhood, Núñez de Cáceres showed

great love for his education but his father was

a farmer and wanted his son to dedicate himself

to also working the field. Núñez de Cáceres was

raised in a very poor family. He had to study

using the books of his classmates because he did

not have all the books he needed. He earned some

money helping his aunt sell the doves that an

acquaintance hunted. Despite early obstacles, at

age 23, in 1795, Nuñez de Cáceres got the Civil

Law degree, he formed a distinguished clientele,

and he became a professor at the

University of Santo Tomás de

Aquino.[1]

At the end of the 18th century

Núñez de Cáceres married Juana de Mata Madrigal

Cordero and they had six(?) children:

1/ the first, Pedro, was

born in Santo Domingo on April 2, 1800,

5/ and last, Maria de la Merced, in the

same city, (Santo Domingo) in

1816

When Ñúñez de Cáceres lived in

Camagüey,

Cuba,

other three children were born:

2/ José, the September 9, 1804;

3/ Francisco de Asis, 15 September

1805, and

4/ Gregorio, on June 8, 1809.

[1] |

|

|

|

|

|

3) Ramón Arturo Cáceres

Vasquez

(15

December 1866,

Moca,

Dominican Republic

– 19 November 1911,

Santo

Domingo)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:Search/Ramon_C%C3%A1ceres

-

was the –

Vice

President

under

Carlos

Felipe Morales,

24 November 1903 - 29 December 1905

31st

President of the Dominican Republic

- (1906

– 1911). Cáceres assumed the office in 1906

and was assassinated in 1911,

ambushed by rebels and killed in his car.[1]

Cáceres was the

leader of the

Los Coludos,

also named Red Party.[2]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ram%C3%B3n_C%C3%A1ceres.

His death was followed by

general disorder and, ultimately, by the U.S.

occupation of the Dominican Republic in 1916.[3][4]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Dominican_Republic

In 1906, (Prez.)

Morales resigned, and Horacista vice-president

Ramon

Cáceres became

President. After suppressing a rebellion in the

northwest by Jimenista General

Desiderio

Arias, his

government brought political stability and

renewed economic growth, aided by new American

investment in sugar industry. However, his

assassination in 1911, for which Morales and

Arias were at least indirectly responsible, once

again plunged the republic into chaos. For two

months, executive power was held by a civilian

junta dominated by the chief of the army,

General

Alfredo

Victoria. The

surplus of more than 4 million pesos left by

Cáceres was quickly spent to suppress a series

of insurrections.[20]New

York Times

article -

http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9502EED61030E333A25754C2A9619C94689ED7CF |

Special Internet search for

the name Caceres

Caceres

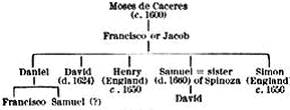

was (also) the name of a Jewish family, members of which

lived in

Portugal,

the

Netherlands,

England,

Mexico,

Suriname,

the

West Indies,

and the

United States.

They came from the city of

Cáceres

in Spain.

Descendants of Moseh de Caceres

G. A. Kohut, Simon de Caceres and His

Plan for the Conquest of Chili, New York, 1899 (reprinted

from the American Hebrew, June 16, 1899).

Name

Cáceres

in other countries of Latin America

(16th – 19th century)

1) Alonso de Cáceres y Retes

– a conquistador,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alonso_de_C%C3%A1ceres

- (born in

Alcántara,

Cáceres,

late fifteenth century - ?) was a ruthless Spanish

conquistador and governor-captain of Santa Marta,[1]

who despite his prolonged military nomadism throughout

the American geography (from

Mexico

to

Peru,

including

Central America),

and his important conquering and peacekeeping ideas, can

be considered one of the most active soldiers who served

in the sixteenth-century Spanish process of conquest.[2]

He was born in the

village of Alcántara (Cáceres), in the late

fifteenth century. He was the son of Gregorio and

Maria Cáceres Retes, had military training and took

part in military interventions in other parts of the old

continent, but his first performances in the American

conquest was exercised after 1530, as a captain

under the command of Governor

Pedro de Heredia,

in southern

Panama

and northern

Colombia,

participating in the foundation of the Colombian city of

Cartagena

de Indias and subsequent interventions as explorer and

conqueror were performed on the

Isthmus of Panama

and on the border Colombia.

On 21 October 1534,

Pedro de Heredia forces under Captain Alonso de Cáceres

command, seized

Acla

and took prisoners for Julián Gutiérre and his wife, the

native Isabel, who knew Spanish and whom Heredia needed

to reach agreement with the Urabá people.

As a man of remarkable

ability, whatever it had been in addition to his

military occupations, he was required for the

administration or the government of the cities where he

lived temporarily. In Santa Marta (Colombia), he served

as

alderman,

in

Yucatan

he served as lieutenant for Francisco de Montejo and

replaced him in the office of

head chief

whenever Montejo was called away, in Arequipa (Peru) he

was appointed mayor and presumably ended his days in

Arequipa enjoying deserved parcels awarded to him.

He married in Lima with

native

creole

María de Solier y Valenzuela, from whose union he had a

son named Diego de Cáceres and Solier, who

married María Mauricia de Ulloa y Angulo in 1581,[3]

from whose union he became grandfather to José de

Cáceres y Ulloa.[4]

Petronila de Cáceres and

Solier,

who first married contrajo matrimonio con Sebastián de

Casalla in 1568 and to Rodrigo de Esquivel y Zúñiga,

whose offspring brought him the marquisate of San

Lorenzo del Valleumbroso.

2)

Francisco Antonio de

Cáceres Molinedo

– Spanish

Governor of Nicaragua

– 1745

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Governors_in_the_Viceroyalty_of_New_Spain

3)

Luís de

Albuquerque de Melo Pereira e Cáceres,

Governador

de Mato Grosso

1772 — 1789,

(Ladário,

21 de outubro

de

1739

—

7 de julho

de

1797)

foi um

militar e

administrador colonial

português. Foi o

quarto governador e capitão-general da

capitania de Mato Grosso

(Brasil).

Tendo tomado posse em 13 de dezembro de 1772,

exerceu o cargo até 1789, sendo sucedido por seu

irmão,

João de Albuquerque de Melo

Pereira e Cáceres. 3)

Luís de

Albuquerque de Melo Pereira e Cáceres,

Governador

de Mato Grosso

1772 — 1789,

(Ladário,

21 de outubro

de

1739

—

7 de julho

de

1797)

foi um

militar e

administrador colonial

português. Foi o

quarto governador e capitão-general da

capitania de Mato Grosso

(Brasil).

Tendo tomado posse em 13 de dezembro de 1772,

exerceu o cargo até 1789, sendo sucedido por seu

irmão,

João de Albuquerque de Melo

Pereira e Cáceres.

http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lu%C3%ADs_de_Albuquerque_de_Melo_Pereira_e_C%C3%A1ceres

-

Durante o seu governo foram erguidos o

Forte de Coimbra

e o

Real Forte Príncipe da Beira,

e fundadas Albuquerque (atual cidade de

Corumbá),

Ladário

(em homenagem à sua terra natal em Viseu), Vila Maria

(atual

Cáceres),

Casalvasco (atual

Vila Bela da Santíssima

Trindade),

Salinas

e

Corixa Grande,

consolidando o domínio português na região diante dos

domínios da Coroa espanhola na América.

4) María Luisa Cáceres Díaz de Arismendi

– (born in Venezuela in 1799, heroine of the War

of Independence) (September 25, 1799 – June 28,

1866) was a heroine of the

Venezuelan War of

Independence. Luisa

was born in Caracas, Venezuela, to José Domingo

Cáceres and Carmen Díaz, prosperous

Criollos.

On her father's side, she was of

Canarian

descent.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luisa_C%C3%A1ceres_de_Arismendi.

5)

José Bernardo Cáceres

-

Battle of Maipu

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Maipu_order_of_battle,

“Patriots” - United Army

Commander: General

José de San

Martín

Commanding officer

of the

2nd Infantry Battalion

- Alvarado'

Division

(Colonel Alvarado),

The

Battle of Maipú

(Spanish: Batalla de Maipú) was a battle fought near

Santiago,

Chile

on April 5, 1818 between

Patriots

and

Royalists,

during the

Spanish American

Wars of Independence.

The Patriots led by José de San Martín effectively

destroyed the Spanish Royalist forces commanded by

General Mariano Osorio, and won the independence of

Chile. 5)

José Bernardo Cáceres

-

Battle of Maipu

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Maipu_order_of_battle,

“Patriots” - United Army

Commander: General

José de San

Martín

Commanding officer

of the

2nd Infantry Battalion

- Alvarado'

Division

(Colonel Alvarado),

The

Battle of Maipú

(Spanish: Batalla de Maipú) was a battle fought near

Santiago,

Chile

on April 5, 1818 between

Patriots

and

Royalists,

during the

Spanish American

Wars of Independence.

The Patriots led by José de San Martín effectively

destroyed the Spanish Royalist forces commanded by

General Mariano Osorio, and won the independence of

Chile.

6)

Andrés Avelino Cáceres Dorregaray

– President of Peru (x3) – 1883-1885, 1886-1890,

1894-1895

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9s_Avelino_C%C3%A1ceres.

Andrés

Avelino Cáceres Dorregaray

(November 10, 1836 – October 10, 1923) was

three times

President of Peru

during the 19th century, from 1884 to 1885, then

from 1886 to 1890, and again from 1894 to 1895.

In Peru, he is considered a national hero for leading

the resistance to

Chilean

occupation during the

War of the Pacific

(1879–1883), where he fought as a

General

in the

Peruvian Army.

Andrés Avelino Cáceres was born on November 10, 1836, in

the city of

Ayacucho.[2]

His father, Don Domingo Cáceres y Ore, was a

landowner

and his mother, Justa Dorregaray Cueva, daughter of the

Spanish colonel Demetrio Dorregaray. He was

mestizo;

one of his maternal ancestors was Catalina Wanka, an

Incaica-Wanka princess. He studied at the Colegio San

Ramón (Spanish:

San Ramón School)

in his hometown. 6)

Andrés Avelino Cáceres Dorregaray

– President of Peru (x3) – 1883-1885, 1886-1890,

1894-1895

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9s_Avelino_C%C3%A1ceres.

Andrés

Avelino Cáceres Dorregaray

(November 10, 1836 – October 10, 1923) was

three times

President of Peru

during the 19th century, from 1884 to 1885, then

from 1886 to 1890, and again from 1894 to 1895.

In Peru, he is considered a national hero for leading

the resistance to

Chilean

occupation during the

War of the Pacific

(1879–1883), where he fought as a

General

in the

Peruvian Army.

Andrés Avelino Cáceres was born on November 10, 1836, in

the city of

Ayacucho.[2]

His father, Don Domingo Cáceres y Ore, was a

landowner

and his mother, Justa Dorregaray Cueva, daughter of the

Spanish colonel Demetrio Dorregaray. He was

mestizo;

one of his maternal ancestors was Catalina Wanka, an

Incaica-Wanka princess. He studied at the Colegio San

Ramón (Spanish:

San Ramón School)

in his hometown.

7) Luis Caceres -

The

Governor

of the

Argentine

province

of

Córdoba,

which is the highest executive

officer of the province-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Governor_of_C%C3%B3rdoba

Name Cáceres

in Latin America

– Contemporary, prominent politicians

1)

Ramón Cáceres Troncoso

–

1964, Council of

State (Triumvirate) of the Dominican Republic

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ram%C3%B3n_Tapia_Espinal

–

Ramón Tapia Espinal was a

member of the Council of State (1961-1963) which

succeeded the overthrow of the dictator

Rafael Leónidas

Trujillo in 1961.[1]

He later served as a member of the triumvirate, a

three-man civilian executive committee, established by

the military after the overthrow of President

Juan Bosch

in 1963; originally with

Emilio de los Santos

and

Manuel Enrique

Tavares Espaillat, and

later with

Donald Reid Cabral

and

Manquel Enrique

Tavares Espaillat.[2]

He resigned from the triumvirate in 1964 and was

succeeded by

Ramón Cáceres

Troncoso.[3]

2) Eduardo Cáceres

– Vice President of Guatemala,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eduardo_C%C3%A1ceres

-

Eduardo Rafael Cáceres Lehnhoff

served as

Vice President of Guatemala

from 1 July 1970 to 1 July 1974 in the

cabinet of

Carlos Arana.

Died 31 January 1980 in the

Burning of the Spanish Embassy

in Guatemala-City[1]

3)

Marina Isabel Caceres de Estevez

– 2008, Dominican Republic, Ambassador

to Denmark, Sweden and Finland - Non-resident Heads of

Missions -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_heads_of_missions_from_the_Dominican_Republic

4) Félipe Caceres

– Bolivia, Vice Minister of Social Defense

in the government of Juan Evo Morales (the presidential

candidate of MAS-IPSP - Movement for Socialism -

Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the Peoples

- a

Bolivian

political movement led by

Evo Morales),

after he won the general election in 2005.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Movement_for_Socialism_%E2%80

93_Political_Instrument_for_the_Sovereignty_of_the_Peoples.

Since taking office, the MAS-IPSP government has

emphasized modernization of the country, promoting

industrialization, increasing state intervention in the

economy, promoting social and cultural inclusion, and

redistribution of revenue from natural resources

through various social service programs.[32]

MAS-IPSP evolved out of

the movement to defend the interests of

coca

growers. Evo Morales has articulated the goals of his

party and popular organizations as the need to achieve

pluri-national unity, and to develop a new

hydrocarbon

law which guarantees 50% of revenue to Bolivia, although

political leaders of MAS-IPSP recently interviewed

showed interest in complete

nationalization

of the

fossil fuel

industries.

Puerto Rico

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puerto_Rico

Map of Puerto Rico in 1639

When Columbus arrived in

Puerto Rico during his second voyage on November 19,

1493, the island was inhabited by the Taíno. They

called it Borikén (Borinquen in Spanish

transliteration).[h]

Columbus named the island San Juan Bautista, in honor of

the Catholic saint,

John the Baptist.

Juan Ponce de León,

a

lieutenant

under Columbus, founded the first Spanish settlement,

Caparra,

on August 8, 1508. (Caparra is an

archaeological site

in the municipality of

Guaynabo, Puerto Rico.)

In the beginning of the 16th century, the

Spaniards

began to colonize the island. (…) During the late 17th

and early 18th centuries, Spain concentrated its

colonial efforts on the more prosperous mainland North,

Central, and South American colonies. The island of

Puerto Rico was left virtually unexplored, undeveloped,

and (excepting coastal outposts) largely unsettled

before the 19th century. (…)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Puerto_Rico

In 1809, to secure its political bond

with the island and in the midst of the European

Peninsular War,

the

Supreme Central Junta

based in

Cádiz

recognized Puerto Rico as an overseas province of Spain.

It gave the island residents the right to elect

representatives to the recently convened

Spanish parliament

(Cádiz Cortes), with equal representation to mainland

Iberian, Mediterranean (Balearic Islands) and Atlantic

maritime Spanish provinces (Canary Islands).

Ramon Power y Giralt,

the first Spanish parliamentary representative from the

island of Puerto Rico, died after serving a three-year

term in the Cortes. These

parliamentary and constitutional reforms

were in force from 1810 to 1814, and again from 1820 to

1823. They were twice reversed during the restoration of

the traditional monarchy by

Ferdinand VII.

Nineteenth century immigration and commercial trade

reforms increased the island's ethnic European

population and economy, and expanded Spanish cultural

and social imprint on the local character of the island.

(…)

In the early 19th

century, Puerto Rico had an independence movement which,

due to the harsh persecution by the Spanish authorities,

met in the island of St. Thomas. The movement was

largely inspired by the ideals of

Simón Bolívar

in establishing a

United Provinces of New Granada,

which included Puerto Rico and Cuba. Among the

influential members of this movement were Brigadier

General

Antonio Valero de Bernabe

and

María de las Mercedes Barbudo.

The movement was discovered and Governor

Miguel de la Torre

had its members imprisoned or exiled.

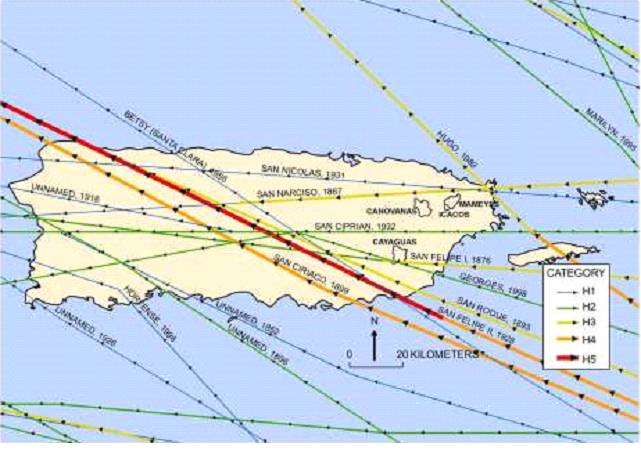

Hurricanes in Puerto Rico

With the increasingly

rapid growth of independent former Spanish colonies in

the South and Central American states in the first part

of the 19th century, the Spanish Crown considered Puerto

Rico and Cuba of strategic importance. (…) Hundreds of

families, mainly from

Corsica,

France,

Germany,

Ireland,

Italy and Scotland, immigrated to the island.[38]

Free land was offered as an incentive to those who

wanted to populate the two islands on the condition that

they swear their loyalty to the Spanish Crown and

allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church.[38]

(…) In 1897,

Luis Muñoz Rivera

and others persuaded the liberal Spanish government to

agree to Charters of Autonomy for Cuba and Puerto Rico.

(…) On July 25, 1898, during the

Spanish–American War,

the U.S. invaded Puerto Rico with a landing at

Guánica.

As an outcome of the war, Spain ceded Puerto Rico, along

with the

Philippines

and

Guam,

then under Spanish sovereignty, to the U.S. under the

Treaty of Paris.

Spain relinquished sovereignty over Cuba, but did not

cede it to the U.S.[47]

(…) In 1917, the U.S.

Congress passed the

Jones-Shafroth Act,

popularly called the Jones Act, which granted Puerto

Ricans U.S. citizenship.[53]

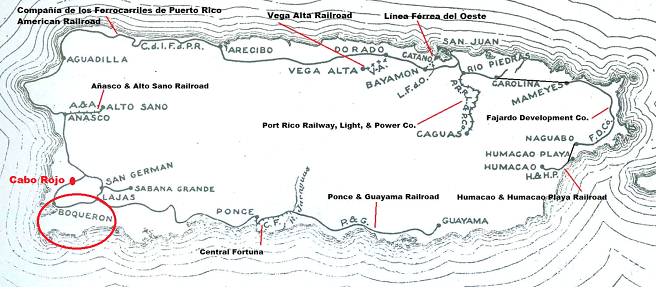

Railroads in Puerto Rico

(end of 19th and 1st half of the

20th century)

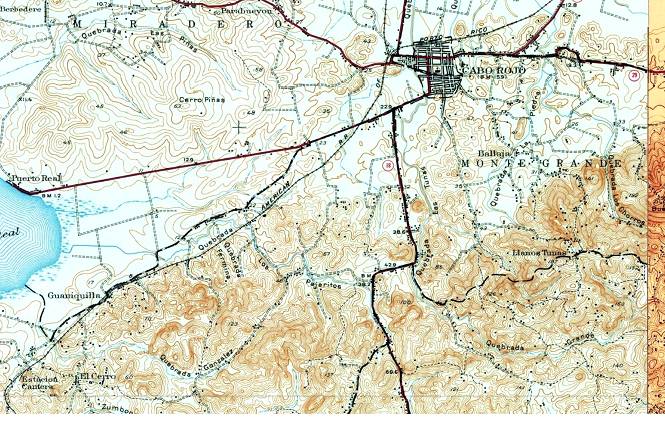

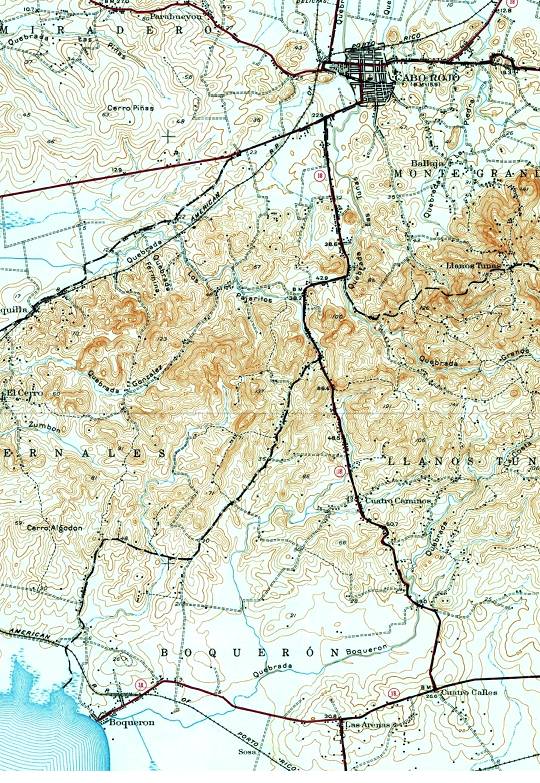

Detailed maps of the Cabo Rojo region

Cabo Rojo and Boqueron

Cabo Rojo

(Spanish

pronunciation: [ˈkaβo

ˈroxo])

is a

municipality

situated on the southwest coast of

Puerto Rico

and forms part of the

San Germán–Cabo Rojo metropolitan area.

(…) Despite the threat of pirates and Indians, the

Spanish settled the area of Los Morrillos around 1511.

By 1525,

salt mining

was an important industry in the area. (…) Cabo Rojo was

founded on December 17, 1771 by

Nicolás Ramírez de Arellano,

a descendant of Spanish nobility. (…) Boquerón is

a beach village located in the town of

Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico.[1]

The village is one of the main tourist attractions in

the southwestern part of the island.[2]

Summary

1) Name Cáceres

in old Spain

Ancestors

(?) of

Diego de Cáceres y Ovando and of the

Conquistador

Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres:

Juan

Blázquez de Cáceres,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Bl%C3%A1zquez_de_C%C3%A1ceres

the

Conqueror of Cáceres,

who was a

Spanish

soldier and nobleman. Juan Blázquez de Cáceres was born

in

Ávila

and was at the Conquest of

Cáceres

(from the Arabs), on April 23, 1229, from which

he took his surname. He was married to Teresa Alfón and

had at

least one son –

Blazco Múñoz de Cáceres,

who died at 90 years and lived in

Cáceres

in 1270,

married to

Pascuala Pérez, daughter of Pascual Pérez and wife Menga

Marín, parents of -

Blazco Múñoz de Cáceres,

Founder

and 1st Lord of the Majorat of the same name, and

García Blázquez de Cáceres,

who by one Marina Pérez had -

Fernán Blázquez de Cáceres,

2nd

Lord

of the

Majorat

de Blazco Múñoz. They

were the ancestors

of the Marqueses de

Alcántara

(de Villavicencio del

Cuervo, May 13,

1667).[1]

---- ??? ---

Immediate Family of the Conquistador

of Hispaniola - Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres

Diego Fernández de Cáceres y Ovando,

1st Lord of the

Manor House

del Alcázar Viejo, and his first wife Isabel Flores de

las Varillas – sons:

Diego de Cáceres y Ovando,

first-born son of Diego and his first wife Isabel

Flores de las

Varillas,

a distant relative of

Hernán Cortés.

Fray

Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres,

The Conquistador

(born -

Brozas,

Extremadura,

1460 –

Died in

Madrid,

May 29, 1511), second son of

Diego Fernández de Cáceres y Ovando

and his

first wife Isabel Flores de las Varillas.

--- ??? ---

2)

Cáceres

names in Hispaniola/Santo Domingo

José Núñez

de Cáceres Albor

–

(born in [the city of] Santo Domingo in 1772,

died in 1846 in Mexico.

President of Spanish Haiti,

December 31, 1821 –

February 9, 1821

Manuel

Altagracia Cáceres

y Fernandez

– (born

Azua Province,

1838

- died 1878)

President

of the Dominican Republic,

3 January 1868

-

13 February 1868

General-in-Chief,

22 January 1874

-

6 April 1874.

Ramón

Arturo Cáceres Vasquez

-

(born 15 December 1866,

Moca,

Dominican Republic

– assassinated 19 November, 1911, [city

of]

Santo Domingo)

–

President of the Dominican Republic

-

(1906–1911)

3)

Cáceres

names and Family in Puerto Rico (Cabo Rojo)

Alonso de

Cáceres

– 1521, a “mayordomo” of the San Juan Cathedral

(the year of its construction)

--- ? ---

Felipe Cáceres-? /Inocencia Vasquez-? (? - ?) - from

Cabo Rojo, P.R.

Juan de Dios Cáceres-Vasquez/Carmela Martinez-Colberg

(? - ?) (Barrio de Pedernales)

Juan de Dios Cáceres-Vasquez/Carmela Martinez-Colberg

(? - ?) (Barrio de Pedernales)

Juan Silvestre Cáceres-Martinez (1897-1972)/Carlina

Ortiz-Ramirez-(Mercado) (1904-1968)

Juan Silvestre Cáceres-Martinez (1897-1972)/Carlina

Ortiz-Ramirez-(Mercado) (1904-1968)

Conclusions

Name Cáceres

in the “New World”

1)

It can be assumed that the paternal last name Cáceres

originates from the Province of Extremadura in

Spain, but it cannot be now determined, whether

people arriving here and bearing this last name were

born in the region (province) of Cáceres

or in the town itself. The name Cáceres

dates back in Spain to the 13th century.

2)

The ancestor of Nicolás Ovando y Cáceres, who

came to this continent and became the first Spanish

governor of the (West) Indies in 1502,

was born in Brosaz, (Extremadura?) in

1460. His ancestor Juan Blázquez de Cáceres

was born in

Ávila.

He was a

Spanish

soldier and nobleman and was at

the Conquest

of Cáceres,

(province and/or town? - from the Arabs), on

April 23, 1229, from which he took his surname

and title “de Caceres” (and passed it on to

his successors).

3)

It can be assumed that all persons “of importance” –

conquistadors/conquerors and administrators

(Governors, Viceroys) belonged to the nobility. They

were:

Nicolás Ovando y

Cáceres

(see above – came to the West Indies);

Alonso de Cáceres y

Retes,

(born in

Alcántara,

Cáceres

in late fifteenth century) was since around 1530,

a

conquistador of Central and South America;

Francisco Antonio

de

Cáceres Molinedo

–

born (?), was a Spanish

Governor of Nicaragua

– 1745;

Luís de

Albuquerque de Melo Pereira e Cáceres,

(and his brother João, both were - )

Governador de Mato Grosso,

Brasil from 1772 to 1789 - they were

born in contemporary Portugal

(across from Extremadura).

4)

Ancestry of others, (who were found in the

Internet), and who were born later, already outside

of Spain (“criollos”), could not be established.

They could have been of a noble descent or

professionals, tradesman or “commoners”, who

accompanied the Conquistadors during settling and

administration of the conquered lands. They could

have been using the same last name to signify that

they also came (from) “de Caceres”. We would need an

expert opinion in this matter. To this group belong:

María Luisa Cáceres

Díaz de Arismendi

– born in Venezuela in 1799, (of

Canarian descent)

José Bernardo

Cáceres

–

born in Chile (?), junior

commander in the battle of Maipu, Chile in

1818

Andrés Avelino Cáceres

Dorregaray

– born in Peru in

1836,

President of Chile x3,

1883-1895

Luis Caceres

-

Privisional

Governor

of the

Argentine

province

of

Córdoba

–

1866

Caceres in

Hispaniola/Santo Domingo (SD)/Dominican Republic(DR)

José Núñez de

Cáceres Albor

–

(born SD in 1772, died in 1846

– Mexico). President - 1821

Manuel

Altagracia Cáceres

y Fernandez

– (born

SD in 1838, died in 1878).

President - 1868

Ramón Arturo

Cáceres Vasquez

- (born DR in 1866, assasinated in

1911). President -

1906-1911

Caceres in Puerto Rico

So far, we have found

only one early entry of this name during our search

in Puerto Rico. This was:

Alonso de

Cáceres

– in 1521, a “mayordomo” of the San Juan

Cathedral (the year of its construction).

We have no information

about his descendants.

Puerto Rico was claimed by

Christopher

Columbus

for Spain during his second voyage to the Americas

on November 19, 1493, (the Spanish settled

the area of Los Morrillos [Cabo Rojo] around

1511). No other details are available to us.

Verbal Information

obtained from the family describes three earlier

generations of this family (exact birthdates are not

known), which gets us back to around the middle of

the 19th century, when they already lived

in Cabo Rojo. There are no other known

records about any other family branches. Perhaps,

the ancestors of this family arrived from Santo

Domingo at the beginning of the 19th

century – escaping the political instability,

oppression, danger to their lives, land

expropriations, and collapse of the economy.

We were unable to make

any direct connections with the Caceres families

discovered in the Dominican Republic – but, also

based on the initial location of the family in Cabo

Rojo (a short distance from the shores of Santo

Domingo), it should be considered that they may have

come from there.

Destruction and loss of

property and income resulting from several

hurricanes and an earthquake, which devastated this

part of the island during the early part of the 20th

century, may have caused subsequent migration to the

North Coast, to the San Juan area.

Or, are they

descendants of earlier Spanish settlers, who arrived

here in 1511?)

Christopher Columbus landing on the

island of Hispaniola in 1492.

1)

Gen. W³adys³aw Franciszek

Jab³onowski;

2)

Although he unofficially led the nation politically

during the revolution, Toussaint L'Ouverture is

considered the father of Haiti.

3) Jean Jacques

Dessalines

became Haiti's first emperor in 1804

|